[ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ]

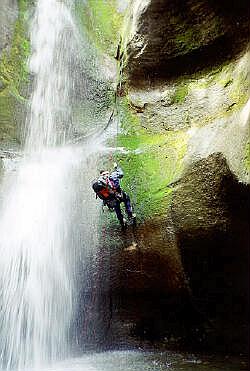

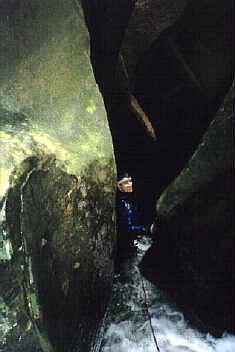

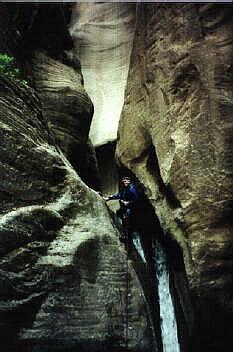

The group of adventurers consisted of three men and five teen-age boys, Explorer Scouts from a Mormon Church in Salt Lake City, Utah. The group thought they were well prepared to explore Utah's backcountry. The adventure began as fun and games, but ended in a Utah morgue. Kolob Canyon is unique. An irrigation dam above the canyon controls the stream flow into Kolob. Washington County Water Conservancy District controls the release of water that flows through Kolob Creek and into the Virgin River. They release a dribble of water most of the summer, when the canyon would otherwise be dry. The potholes and plunge pools are always full of clean, clear and very cold water. Before entering Kolob Canyon the group had camped together many times and practiced basic canyoneering techniques like hiking in streams and climbing rocks with the aid of ropes. The group was equipped with wetsuits to insulate their bodies from the chilly water of the canyon. They had obtained a Zion Backcountry Permit from the National Park Service; the only official government contact required when exploring the backcountry of Zion. Their 28-year-old leader David Fleischer had done the hike twice previously. The group was very confident in their abilities . On the morning of July 15 1993, dressed in wetsuits, their gear stored in drybags, the three men and five boys dropped into the canyon. The group rappelled down 75-feet of vertical sandstone cliff, into the confines of Kolob Canyon. The canyon is a deep slot with narrow bends and deep pools of icy water. The creek eventually feeds into the North Fork of the Virgin River and Zion National Park.

Almost immediately, the adventurers must have sensed trouble. They had expected some water in the canyon. They had anticipated that hiking the streambed would require rappelling down a series of waterfalls and past plunge pools. But the water was too fast and too deep. Where they had expected it to be ankle-deep, it was up to their knees. Down at the bottom between the sheer sandstone walls, all that water rushing and tugging at them was very loud. It was difficult to communicate above the noise of the stream. Safe water conditions are considered to be a flow rate of 5 cubic feet per second (cfs) or less, the river was flowing at 29 cfs. Fleischer had been concerned about water levels before entering the canyon and had checked with park officials several times in advance. Once Fleischer got down into the canyon, he was angry that park rangers had not been more clear about the danger. When the men and boys found themselves in such surprisingly high water, Fleischer raged that it was "ludicrous" they had been granted a permit. The group kept walking with the current and negotiated several waterfalls and obstacles. Fleischer knew where there might be some dry ground ahead, if the hikers could make it past a raging series of four waterfalls. The first waterfall dropped off eight feet. Fleischer kept the lead, rappelling over the edge, but a whirlpool at the base snared him. Unable to disconnect from his rappel rope with the torrent of water crashing down, Fleischer had little freedom of movement. The boys began yelling that they could see that his backpack strap had slipped around his neck and was choking him. Kim Ellis, 37 years old, leaped in and managed to free Fleischer from the grip of the whirlpool, but Ellis banged his head on a rock and got sucked to the bottom. The third adult, Mark Brewer, 35 years old, leaped in and managed to wrestle Ellis and himself from the pool. Thirty minutes of CPR was futile. Ellis was dead. The two surviving men decided to proceed, which was their only known exit from the canyon. They propped Ellis' body against a log and rigged a rope to lower the boys from the lip of the falls. The first boy lowered was the dead man's 14-year-old son. There was no place to rest as the stunned canyoneers struggled on. The group used ropes to maneuver over two waterfalls. When they reached the fourth falls, they had been in the water two hours and had made only 150-feet of downstream progress. The group had lost 6 of their 8 backpacks and much of their rope. The fourth falls was taller, cascading 15-feet.

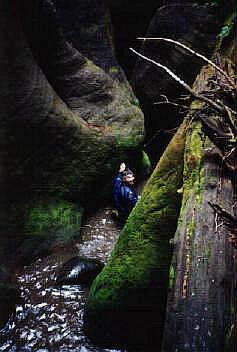

From the rim of the falls, Fleischer tested the force of the whirlpool at its base. He tied a rope to his pack and tossed the pack into the pool. The pack got sucked under and could not be pulled free. Fleischer decided he had to free the pack. He intended to swim the pack to shore where it could serve as a safety anchor for the others. He leaped in, and just when it seemed he had everything under control, the pack slipped and the current sucked him under. There was a long moment as the others stared down into the churning torrent. Fleischer never reappeared. As the last remaining adult, Brewer was left with a very difficult decision, which had to be made immediately. He had to decide whether to stay with the boys or risk himself further by trying to save his friend. The boys were scared, confused and shivering with cold. Brewer told the boys Fleischer was probably dead. He backed them away from the falls and told them there was no choice, they had to wait where they were and hope for rescue. The group was down to Brewer and the five boys. They pulled rocks from the stream and built a small ledge they could rest on. When fatigue overtook them, they slept piled on each other. Waiting it out for five days and four nights, they sustained themselves on small rations of raisins, candy and oatmeal packets. The canyon was 1,300 feet deep and so narrow that they received less than one hour of direct sun each day. The group sang songs and prayed against the damp chill. They knew that sooner or later it would be noticed that they were overdue, and a search would begin. They had three matches and wasted two trying to light some driftwood for a signal fire. Helicopters flew over the narrow slot of sky above, and they heard searchers calling. However, no one responded to the group's shouts for help. They used their last match to ignite a signal fire from their salvaged supplies, but they were too far down and the smoke wasn't noticed. Late on the afternoon of July 19, five days after entering the canyon, the end of a rope mysteriously snaked down into the pool in front of them. The local search and rescue team, the local sheriff's office and Zion National Park had arrived to rescue them. A helicopter shuttle took the group to Zion. Ellis' body was also recovered. Two of the survivors were treated at a local hospital for edema in their legs and feet, which had been brought on by the prolonged wearing of the tight wetsuits. Searchers working their way carefully up the canyon bottom didn't locate Fleischer's body until 11 days later. The popular view is that the boys and their three adult leaders were not well enough prepared and the two leaders died because they made mistakes. Zion Park officials maintain the church group was properly informed of the inherent dangers and difficulty of a Kolob Canyon descent. Fleischer's permit was marked with a "high" danger rating. During periods of "high" danger, rangers can only recommend against expeditions, legally they cannot refuse a permit. Zion Park officials had informed the group that a decent of Kolob Canyon would be difficult, dangerous and time consuming, which many consider an integral part of the backcountry experience. Warning: Related Link: [ Homepage ] [ Introduction ] [ Warning ] [ Ratings ] [ Ethics ] [ Feedback ] [ Updates ] © Copyright 1999-2002, Shane Burrows |